And so it begins…

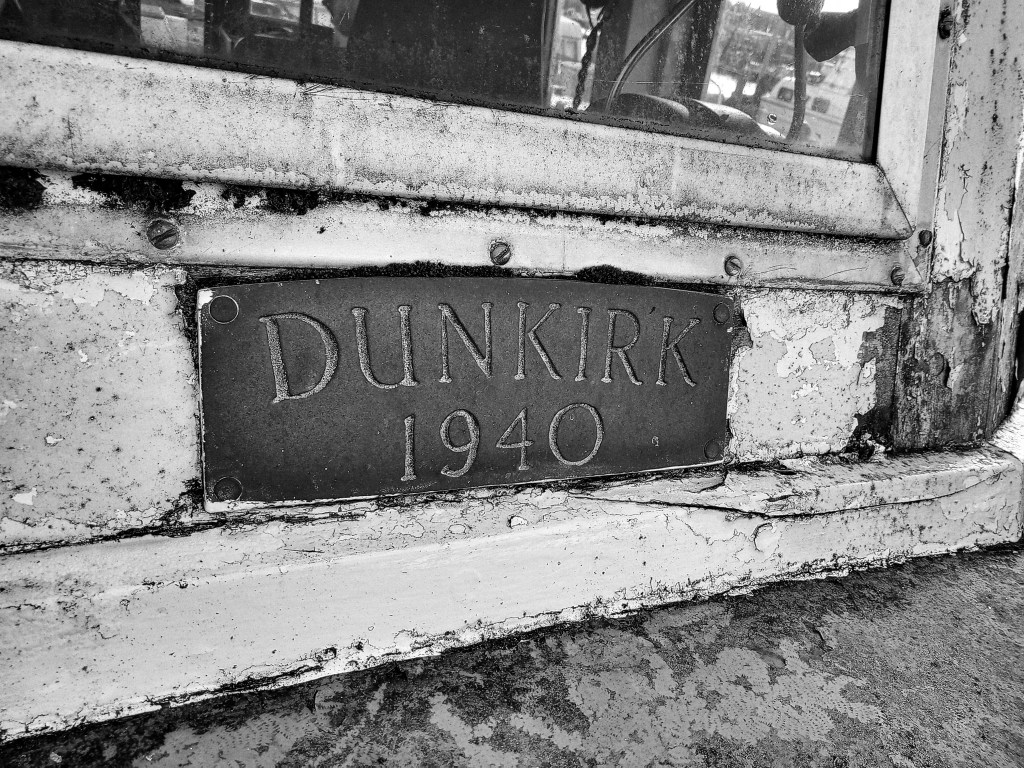

At the time of writing this, it is February 2024. I have been the owner of Dowager for a little over two weeks, yet I am amazed I was able to get anywhere near her in the first place, let alone actually own what amounts to be a priceless piece of our maritime history.

I won’t lie – I know as much about seafaring as Captain Birdseye. My mechanical background is in bikes and cars. Give me an engine, and I’ll strip it down and rebuild it. Ask me to repair a braking system, and I’ll do that too. In my career, I have designed and assembled pneumatic systems capable of achieving 1000 bar. I can build a shed from a pile of timber, install a rudimentary plumbing system, do some basic rewiring, and even put up a shelf.

But I have never in my life fixed up a 41ft yacht that is over 90 years old. In fact, I almost failed my GCSE Woodwork at school, having scraped a grade C thanks to some last minute panicking over a lathe. In short, I can understand the perception that having me take on the restoration of Dowager is like having your local furniture joiner tackling the HMS Victory.

Now where’s that orbital sander?

The Ultimate Aim

The aim of my planned restoration of Dowager is exactly that – to restore, rather than replace what’s left. There are things I really like about her current state; things like the deck toe-boards that have shrunk from over-exposure to the sun, exaggerating the grain of the wood. I could simply strip them out and replace them with a more modern design. But some fine sanding, treating, sealing and painting is all they need to help retain the ship’s past character as a lifeboat. The same too goes for her original Sampson posts capped in bronze.

“…you realise the boat isn’t really waiting, but sleeping under so much moss and mould.”

And yet there are things I don’t like so much, such as the plywood boards on her deck that have softened and let in water. I’m already thinking of giving Dowager back her mahogany deck to match her wonderful hull planking.

More than a foot of water had found its way inside the boat, and the first job was to drain as much out as possible. I had been advised that I could drill a hole through the hull – which certainly would have done the job, but the idea of doing so felt like vandalism somehow. Instead I pumped it all – more than 120 gallons – from the lowest point I could find. On my next visit, I’ll be going back with armfuls of absorbent material to soak up as much remaining water as possible, and get the inside of the boat dry (at last).

What matters most to me is retaining all the original pieces that are still there. When you step inside the wheelhouse, you can smell the mineral oil, and you realise the boat isn’t really waiting, but sleeping under so much moss and mould. Down below, almost hidden on an over-painted oak beam, there survives an inscription bearing the ship’s original reported gross weight; a little over 7.5 tonnes.

Seeing it reminded me of something a surveyor said when he realised just what a find Dowager is. He reflected that back when she used to be launched from her lifeboat station to face ferocious storms alone, there was no such thing as GPS navigation, there was no possibility of a helicopter rescue should everything have fallen apart, there were no survival suits, no satellite communication. All the crew had was their skill, their determination, their courage, and each other to make up the difference.

I’ve already learnt and seen a lot since I first clapped eyes on Dowager, yet the most worrying sight of all is that of so many other historic vessels spread across numerous boat yards and marinas that are steadily decomposing to nothing. It seems the skills needed to build and maintain traditional boats are sadly slipping away in this country.

Training colleges struggle to fill their available places while boat yards cry out for skilled labour to keep up with demand. If it is down to idiots like me to pick up and try to preserve these small pieces of British heritage, then all I can say is; God help our history.

Leave a comment